OPINION

Zum zweiten Jahrestag der Aufstände von Jin, Jiyan, Azadi: Gewaltsame Kollektivbestrafung in Rojhelat und autoritäre Resilienz im Iran

Online veröffentlicht von TISHK Zentrum für Kurdistan Studien: 15. September 2024

Hassaniyan, Allan (2024) On the Second Anniversary of the Jin, Jiyan, Azadi Uprisings: Violent Collective Punishment in Rojhelat, and Authoritarian Resilience in Iran. Kurdistan Agora https://tishk.org/blog/kurdistanagora/on-the-second-anniversary-of-the-jin-jiyan-azadi-upris-ings/ .

Zusammenfassung

Dieser Artikel untersucht die gewaltsame kollektive Bestrafung durch die Islamische Republik Iran (IRI) in Rojhelat (Ostkurdistan) nach den Aufständen von der Jin, Jiyan, Azadi Bewegung, die durch die Ermordung von Jina Amini im September 2022 ausgelöst wurden. Die IRI setzte Massenverhaftungen, Hinrichtungen und Militarisierung ein, um den kurdischen Widerstand zu unterdrücken und die autoritäre Kontrolle aufrechtzuerhalten. Am Beispiel der Stadt Jiwanro in Rojhelat wird gezeigt, wie staatliche Gewalt als Instrument autoritärer Resilienz und ethnischer Unterdrückung dient. Der Autor untersucht den historischen Kontext der Beziehungen zwischen Kurden und dem iranischen Staat und die weiterreichenden Auswirkungen der iranischen Politik, die die Rechte der sog. Nicht-Perser im Iran verletzt.

.

Keywords: Kurdish resistance; Iranian authoritarianism; State violence; Jin, Jiyan, Azadi uprising

Introduction

Following the murder of 22-year-old Kurdish woman Jina Amini by the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) on 16 September 2022 and the subsequent uprising and radical condemnation by the Kurdish people, Rojhelat (Eastern Kurdistan) has become a testing ground for this regime’s repressive methods and tactics. The regime has implemented brutal collective punishment of the Kurdish people, including widespread imprisonment and mass execution, as a result of the decrease in protests and its success in regaining control of the streets and other public places.

This essay contends that the IRI employs state violence and collective punishment in Rojhelat for multiple purposes. For instance, this approach serves as a tool for authoritarian resilience. It brutally suppresses the Kurdish demand for change, demonstrating the regime’s ability and willingness to crush any opposition through repressive and violent means.

“Funerals, grieve and collective resistance”

Frequent reports of human rights abuses, including arbitrary arrests, torture, and executions of Kurdish activists, show that these are common practices of the Iranian state in Kurdistan. This condition has contributed to a climate of fear and oppression. The Iranian state’s response to the uprisings, particularly in Rojhelat, involved significant use of violent force, including deploying military and paramilitary units, conducting mass arrests, and using lethal force against protesters. The regime’s harsh response to the protests in Kurdistan reflects a zero-tolerance policy towards any form of challenge to state authority, ideology, and the definition of ‘identity’ in Iran. However, geopolitical interests and the broader context of Middle Eastern politics often muffle the international community’s response to the plight of Kurds in Iran. Such a high level of repression and collective violent punishment is an element of continuity defining the Kurdish-state relationship in Iran.

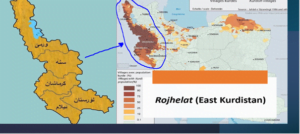

Map of Rojhelat

From Protests to Military Strikes: The Iranian Regime’s Policy of Destruction in Rojhelat

The year 2022 and afterwards mark another historically challenging time for Kurdistan and regions such as Baluchistan, with contrasting ethnic and religious differences from the ruling regime in Tehran. During the 45-year-long reign of Iran’s Islamic regime, people from these regions have been the everyday targets of the IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps) and other regime militias. However, since September 2022, the kidnapping and persecution of male and female civic, environmental, and cultural activists have increased significantly, though collective civic resistance and mass protest have been the only measures to challenge the region’s authority in these regions.

From right is Jina Amini and her grave

For instance, Kurdistan held six general strikes, totalling more than twenty-five days, in the early two months following Jina Amini’s murder, shutting down all shops and businesses in protest against the regime’s use of lethal violence and the killing of several hundred Kurdish protesters. In retaliation for the Kurds’ pioneering role during the uprising known as Jina’s Revolution, the Islamic regime has intensified its systematic de-development and destruction policy in Kurdistan, including intensifying its ecocide policy and besieging Kurdish cities and towns.

These policies aim further to impoverish the already socioeconomically and politically marginalised Kurdish region. Kurdish provinces in Iran have long been the most militarised areas, with every element of daily life scrutinised and approached through security-oriented lenses. This situation has further deteriorated Rojhelat’s sociopolitical condition. Repeated instances of forest fires initiated by the IRGC have destroyed the once-beautiful forests and landscape, showing the regime’s determination to destroy Kurdistan and punish the Kurdish people in Rojhelat collectively for their anti-regime actions. Moreover, using these measures, the regime aims to use Kurdistan as a model of punishment to quell critical voices across other parts of Iran. The state’s use of collective violence in the post-2022 uprisings in Rojhelat is a chronic issue that stems from historical and ethnic tensions, security imperatives, and political strategies. This requires urgent attention to stop the regime’s violation of the Kurdish people’s human rights in Rojhelat.

Understanding this regime violence requires an appreciation of the historical Kurdish-state relationship in Iran, the deep-seated grievances of the Kurdish people, and the Iranian state’s prioritisation of maintaining control and suppressing any form of opposition. The contemporary Kurdish-state relationship during the reign of the Islamic regime has many records of besieged Kurdish cities, starting in the 1979-1980s. The regime used the same post-1979 revolutionary era’s violent and repressive tactics of collective punishment. During and after the Jina Revolution, numerous cities in Rojhelat faced intense military operations and periods of siege.

On the left are two Kurdish female peshmerga fighters, and the image of the rights is a big Kurdish ‘No’ to the Referendum of the Islamic Republic on 30 March 1979.

The Massacre in Jiwanro, a Defenceless and Besieged City

Particularly following the 2022-2023 uprisings, the regime’s use of collective punishment in Rojhelat has been so severe that every city of Rojhelat can be a case study. However, the November 2022 mass killings of protesters in Jiwanro (in Persian; Javanrud), a town in the Kurdish province of Kirmashan (in Persian: Kermanshah), are a well-documented example of regime brutality, collective punishment, and indiscriminate violation of human rights in Kurdistan. This essay considers this brutal incident as a case study. For instance, the Centre for Human Rights in Iran and the Kurdistan Human Rights Network documented the regime’s violent attack on civilians in Jiwanro in their 100-page report, “Massacre in Javanrud, State Atrocities Against Protesters in Iran’s Kurdish Region”. This insult caused at least eight deaths and between 80 – 100 critically injured individuals. This brutality occurred after a peaceful protest in Jiwanro, during which the regime’s armed forces, including the IRGC and other militias, terrorised the people in this city for six months.

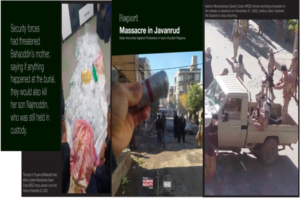

Massacre in Jiwanro, State Atrocities Against Protesters in Iran’s Kurdish Region

Jiwanro’s condition began to deteriorate in early October 2022. The city gradually transformed into a war zone, and by late November, the IRGC intervened intensively and began to open fire directly on the people. The regime’s assault occurred with extreme brutality, as it was engaging in combat with foreign troops, revealing the Iranian state’s colonialist behaviour in Kurdistan. The regime’s armed forces consistently used military-grade weapons to shoot at protestors. The urban environment underwent a drastic shift, becoming a site of intense conflict, as a well-equipped and ruthless state military force utilised heavy weaponry such as DShK (Doshka) and other machine guns and conventional warfare tactics against unarmed civilians. In response, civilians fought back against the regime’s armed forces, by protesting and throwing stones. The conflict was significantly unequal in all aspects. On the other hand, there was also a ‘Battle for the Bodies’ of those killed by the regime. This condition refers to a situation in which the regime consistently attempted to confiscate the bodies of the victims to prevent the families from conducting burial rites that would bring attention to the state’s killing.

To the left is a life bullet used against the protester (Jiwanro, 21 November 2022). To the right is an IRGC checkpoint in Jiwanro.

To further increase the level of cruelty, the regime sent military vehicles and soldiers from neighbouring cities and provinces to Jiwanro. By late November, the IRGC and other gunmen of the regime had taken control of all the city’s exits. They established checkpoints that remained in place until March 2, 2023. The intense climate of fear that pervaded the city, the continued heavy presence of IRGC forces, and the mass shootings on December 31, 2022, deprived the residents of Jiwanro to carry on a normal life. In response to the anti-regime protests by the citizens of Jiwanro, the IRGC implemented a four-month siege of the town as a form of collective punishment and vengeance. As stated in the report, “until early March 2023, Javanrud remained under a crippling four-month siege by security forces as punishment for the protests. Control over the movement of vehicles in and out of the city not only impeded the provision of assistance to the wounded but also directly affected the daily lives and livelihoods of many people in Jiwanro. A significant portion of the city’s economy relies on its market for border trade, where people from other cities and provinces go shopping and trade, as Jiwanro’s bazaar is one of the region’s largest border markets”.

The IRGC stationed at all the city’s entrances obstructed the passage of all commodities purchased from Jiwanro’s ‘border’ market. The entire city, beset by significant unemployment, endured a comprehensive economic and military siege intended to punish the entire population and exact revenge for the protests. The regime’s intelligence and armed forces were stationed both inside and outside the medical facilities to identify the injured demonstrators. This posed a significant challenge to the injured individuals who participated in the protests in Jiwanro, since they could not seek medical treatment in the city’s hospital due to the potential threat of arrest. By November 21, the presence of at least 200 extra men from the IRGC in the city caused a significant escalation of these concerns.

While the citizens of Jiwanro attempted to provide emergency medical assistance to the injured individuals, their efforts were futile due to the massive presence of the advancing IRGC and the constant barrage of machine-gun fire. Due to the exceedingly large number of injured, a significant portion of the wounded could only obtain very basic medical care while still on the streets. Individuals who made efforts to provide medical care to the wounded on the streets faced the peril of being deliberately shot by the regime’s IRGC and militias, and they also feared being apprehended for their aid. Families that attempted to provide shelter and treatment for the injured inside their homes also ran the risk of arrest. As stated by the report this inhuman condition meant that the city’s hospital was the most remote location in the world. By late November 21, following the IRGC’s total control of Jiwanro, sources recounted that at least 60 injured people were hiding in people’s homes, fearful of being arrested if they sought medical treatment in the city’s medical centres. The IRGC militias warned medical staff not to treat the injured before informing the IRGC in advance.

Continuity of State Repression in Rojhelat

According to the Kurdish human rights organisation Hengaw, following the 2022-23 uprisings, the IRI’s armed and intelligence forces detained at least 745 Kurdish civilians and activists in various Kurdish provinces and Tehran, Khuzestan, Razavi Khorasan, and Mazandaran provinces on political grounds. Hengaw’s report for May 2024 confirmed an increase in the pattern of persecution in Kurdistan, with the Iranian intelligent apparatuses apprehending a total of 141 people. The Kurdish and Baloch national groups constituted more than 70 percent of the detained individuals in Iran. However, it is important to emphasise that the widespread persecution in Kurdistan is not limited to the period of Jina’s Revolution but rather a continuous problem with historical roots. For instance, following the protests in March 2019 and the sudden spike in gas and gasoline prices, authorities detained a minimum of 2,000 civilians from Rojhelat.

The Kurdish case in Rojhelat suggests a relationship pattern defined by state violence and collective punishment within a historical context. This phenomenon is a continuation of the long-standing ‘state of terror and violence’ that characterises the Kurdish-state relationships in Iran. This pattern dates back to the early 1900s, particularly during the first Pahlavi era, and it has persisted into the post-1979 revolutionary period. Comprehending the application of collective punishment on the Kurdish people in Iran necessitates an examination of historical, political, social, and cultural aspects. The Kurds in Rojhelat, like Kurds in other countries that occupy Kurdistan, possess a unique cultural and national identity that differs from the ruling power’s focus on a unified national identity.

Among the primary goals of the modern, post-Enlightenment state are assimilation, homogenisation, and conformity within a relatively narrow ethnic and political range, as well as the creation of societal agreement about the kinds of people there are and the kinds they ought to be. From a historical perspective, investigating the rationales behind states’ use of violence suggests that violent struggles, such as wars of independence, civil wars, revolutions, and the assimilation and destruction of others, have forged many modern nation-states. These conflicts often solidify national identity and centralise state power. State violence can suppress political dissent and rebellion, enforcing a unified national identity. When it comes to nation-state building, state violence is a double-edged sword. While it can contribute to establishing and centralising state power, enforcing national identity, and controlling resources, it also carries the risk of long-term instability, human rights abuses, and delegitimization of the state. The specific outcomes depend on various factors, including historical context, the nature of the state, and the society in which it operates.

Reviewing a century-old Kurdish-state relationship in Iran, similar to other states occupying Kurdistan, reveals the presence of a coloniser-colonised relationship defined by exploitation and violence. It also shows that the relationship between state violence and nation-state building is complex and multifaceted, involving historical, political, sociological, and economic dimensions. Despite Iran’s century-old nation-state, creating a homogenous national identity that includes all national groups residing in its territorial boundary remains uncompleted and, in fact, in its worst shape ever. Successive Iranian regimes’ violent attempts to create a mono-national and homogenous nation-state have failed, but the ruling elite’s continual insistence on completing this task, albeit violently, has resulted in massive violations of the rights of the non-Persian excluded national communities.

One may argue that the Iranian nation-state has existed for a century, and the country’s Islamic regime has, since the late 1980s, established complete control over Rojhelat. But the reality is that even if the regime succeeded in gaining territorial control and defeating the armed section of the Kurdish movement, from the early moment of its creation, it failed to win the hearts and loyalty of the Kurdish people in Rojhelat. Following the violent transition of power from an authoritarian Pahlavi monarchy to a theocratic despotism of IRI, the Iranian Revolution of 1979 did not fulfil any of its promises of freedom and equality. Since the inception of the Islamic Republic in 1979, state-sanctioned violence and terror have consistently targeted all of Iran’s numerous national and religious communities, but mainly the Kurdish people.

The regime’s extensive use of indiscriminate violence and cruelty to quell protests in Kurdistan is unprecedented in other parts of Iran. The deep militarisation of the Kurdish region, the construction of enormous checkpoints, and the imposition of quasi-martial rule highlight the fact that the relationship between the Kurdish people and the state in Iran is one of ‘colonised-coloniser’. When it comes to the regime’s excessive violence and violations of human rights in Kurdistan, the regime’s behaviour reveals that it is still struggling with its unfinished task of nation-state building. This is evidence of failed power consolidation, recasting, and reforging nation-states; the regime has never succeeded in gaining the hearts of the Kurds. An examination of the evolution of state violence and the reign of terror in Iran reveals its critical role in shaping and developing the post-revolutionary state in Iran. However, we should not interpret the Iranian state’s indiscriminate and collective punishment approach towards Kurds as an irrational and haphazard act but rather as a deliberate act and a strategy that is taking place within the context of reforging state-defined identity and regime ideology.

Internationally, the treatment of Kurds in Iran draws attention to broader human rights issues. However, geopolitical considerations, such as Iran’s strategic importance and the complexity of Kurdish demand for self-determination across multiple countries, often result in limited international intervention or solidarity with Kurdish demand for self-determination. However, when it comes to the question of Iran’s exploitation of the Israel-Hamas conflict for Kurdish repression, it receives little to no scrutiny; in the context of the relationship between Western countries and Iran, human rights violations, particularly in Kurdistan, are virtually non-existent. There are several examples of the Iranian regime’s violation of Kurdish human rights, including the regime’s assassination of Dr Abdulrahman Ghassemlou in Viena on July 13, 1989, where Austrian police arrested the assassinators but, in exchange for economic reasons, returned or better to say ‘escorted them’ to Tehran. The Iranians are well aware of the indifference with which the global community views their atrocities and human rights violations. Consequently, they do not consider this factor as significant. Currently, the West is preoccupied with other issues, such as Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile program and the potential impact of Iran’s proxy war and involvement in regional and global subversive activities on regional and international security. Therefore, one can claim that issues related to the violation of human rights in Iran and Rojhelat do not bother the global community greatly.

- Alan Hassaniyan is a dedicated lecturer specializing in Middle East Studies at the Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies (IAIS), University of Exeter. He earned his BA and MA in Arts in Public Administration and International Politics, followed by a PhD in Kurdish Studies from the Centre for Kurdish Studies at the University of Exeter. His doctoral research focused on the 20th-century Iranian-Iraqi Kurdish Movements, studying their cross-border interactions and subsequent effects on mobilization within the Iranian Kurdish Movement. The expertise of Dr. Hassaniyan spans critical historical eras, including the Middle Eastern state and society, the modern history of Iran, politics in Kurdistan, and Iraq’s nation-state building during the Ottoman era. Notably, Hassaniyan’s research and publications, exemplified by his book “Kurdish Politics in Iran Crossborder Interactions and Mobilisation since 1947” published by Cambridge University Press in 2021, delve into the intricacies of Kurdish politics and state securitization in Iranian Kurdistan, shedding light on armed conflicts and popular uprisings in the region.

- This paper was presented at the MESF Joint MESF Webinar with Governance, Development and Peace Research Stream at ADI, “Repressing Kurds by Turkey and Iran Against the Backdrop of War in Gaza” (August 5, 2024). This symposium explored how the Turkish and Iranian states leverage the global attention on the Israel-Hamas conflict to intensify their repression of Kurds (for more details, see https://www.mesf.org.au/event-2024-08-05/ ).

Save PDF

TISHK News